Immunotherapy now spans two headline approaches: oncolytic viruses (OVs) and CAR‑T cells. Both enlist the immune system to fight cancer, yet they differ in how they work, where they’re used, side effects, logistics, and how mature the evidence is. This updated 2025 guide explains each path – clearly and without hype – so you can make informed, practical decisions with your care team.

How they work – at a glance

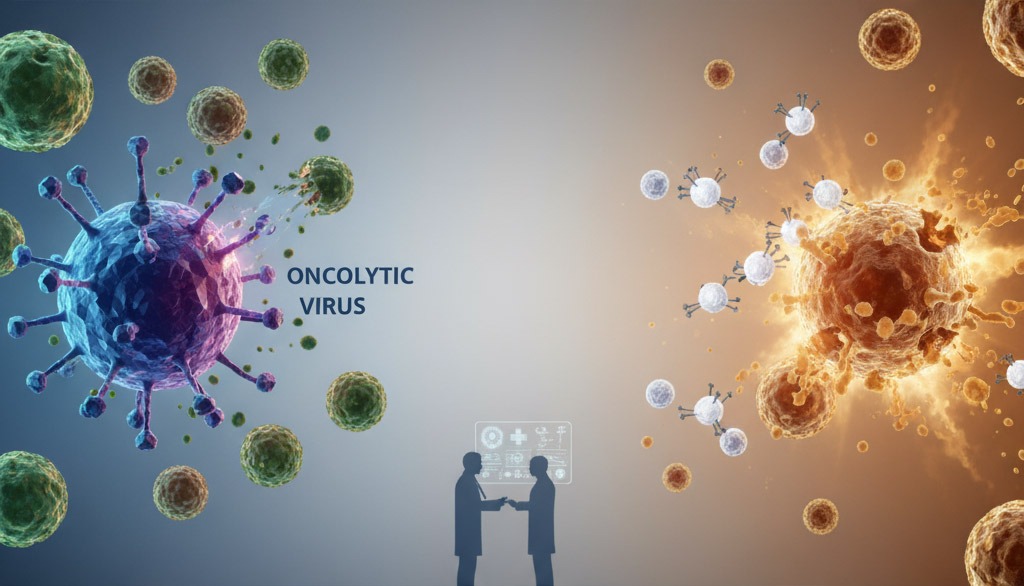

Oncolytic viruses (OVs)

- What they are: Naturally occurring or engineered viruses designed to replicate preferentially in cancer cells.

- How they act:

- Direct oncolysis – infected tumor cells burst.

- Immune priming – the debris “unmasks” the cancer so T cells can mount a broader attack.

- Direct oncolysis – infected tumor cells burst.

- Where they’re given: Most of the time, oncolytic viruses are given intravenously (IV); if the tumor’s location allows, intratumor injections can be performed under CT or ultrasound guidance.

CAR‑T cells

- What they are: A patient’s (autologous) or donor’s (allogeneic, trial‑only) T cells that are engineered with a chimeric antigen receptor to recognize a tumor marker (e.g., CD19, BCMA).

- How they act: After reinfusion, CAR‑T cells bind their target and kill cancer cells; they can expand in the body and patrol for residual disease.

Approvals and access (2025)

| Modality | What is approved today | Where trials are most active |

| OVs | Talimogene laherparepvec (T‑VEC, HSV‑1) for unresectable melanoma (intratumoral). A herpes‑based OV (often cited as G47Δ/teserpaturev) holds conditional approval in Japan for malignant glioma. | Glioblastoma and other solid tumors; many protocols combine OVs with checkpoint inhibitors. |

| CAR‑T | Multiple autologous products for B‑cell cancers (e.g., DLBCL, ALL) and myeloma (BCMA). | Earlier‑line use and streamlined pathways in blood cancers; solid‑tumor CAR‑T remains investigational. |

Key point: As of 2025, no CAR‑T therapy has broad approval for solid tumors, and most OV use beyond melanoma (or Japan’s glioma approval) occurs within clinical trials.

Efficacy signals (what we know so far)

| Question | Oncolytic viruses | CAR‑T cells |

| Where are responses most established? | Melanoma (approved). Durable responses reported in selected glioma trial cohorts; other solid tumors under study. | B‑cell malignancies and myeloma (standard after defined prior therapies). |

| Time to response | Often weeks to months – immune priming takes time; early scans can look worse before they look better (pseudoprogression). | Often 1–4 weeks after infusion; tumor reductions may be rapid. |

| Durability | “Long‑tail” survivors reported in subsets; larger randomized data are emerging. | A meaningful fraction achieve multi‑year remissions; durability depends on disease and product. |

Take‑home: CAR‑T has transformed outcomes in several blood cancers. OVs are advancing in solid tumors – especially in combination with checkpoint inhibitors – but remain investigational in most settings.

Safety profiles you should understand

Oncolytic viruses

- Common: Flu‑like symptoms, fever, fatigue, transient headache; local injection‑site discomfort.

- Less common: Transient lymphopenia or inflammatory flares.

- Rare: Viral encephalitis or serious infection (notably with herpes‑based vectors); managed per protocol with antivirals and/or steroids.

- Practical note: Short inpatient observation is typical around surgery‑adjacent dosing; biosafety procedures minimize any shedding risk.

CAR‑T cells

- Cytokine‑release syndrome (CRS): Fever and low blood pressure are common early events; most cases are low‑grade and respond to tocilizumab ± steroids.

- Neurotoxicity (ICANS): Confusion, difficulty speaking (aphasia), or seizures can occur; close monitoring and prompt treatment are standard.

- Cytopenias / infection risk: Low blood counts can persist; vaccination timing and antimicrobial plans are arranged in advance.

Logistics and patient experience

| Step | Oncolytic viruses | CAR‑T cells |

| Manufacture | Off‑the‑shelf vials prepared under GMP; each lot must pass release testing. | Autologous: leukapheresis → gene transfer → expansion (weeks). Allogeneic: trial‑only; faster but still under study. |

| Treatment setting | Outpatient injections or short hospital stays (perioperative dosing possible). | Usually inpatient for infusion and early monitoring (some centers piloting outpatient models). |

| Re‑dosing | Often repeated (e.g., every 2–3 weeks or per protocol). | Typically a single infusion; re‑treatment is uncommon and product‑specific. |

How doctors choose between them (and how to choose a center)

- Cancer type & target availability

CAR‑T needs a reliable antigen (e.g., CD19/BCMA) with minimal expression on healthy tissue. OVs are attractive for accessible solid tumors, particularly within combination trials. - Disease setting

CAR‑T is standard after specific lines of therapy in several blood cancers. OVs for solid tumors are typically trial‑driven. - Patient fitness & goals

Weigh the monitoring needs and potential toxicities of CAR‑T (CRS/ICANS) against the procedural aspects of OVs (biopsy, catheter placement, perioperative care). - Center expertise & trials

Delivery at experienced centers with active research programs improves access and safety for these complex therapies. Choosing a center with deep expertise in the relevant modality is key. For example, a patient exploring oncolytic-virus trials for a solid tumor such as glioblastoma might consider a specialized program like Biotherapy International (ibiotherapy.com), which focuses on advancing OV-based immunotherapy. Within such programs, professionals like Arthur Portnoy, who combines healthcare facilitation with program development, help streamline eligibility review, logistics, and follow-up, illustrating the value of matching patients to centers with the right, cutting-edge programs.

Team profile: ibiotherapy.com/our-team/arthur-portnoy/

Smart questions to ask your team

- Is there an approved option for my cancer type, or would access be via a clinical trial?

- For CAR‑T: which antigen is targeted, and how likely is antigen loss in my disease?

- For OVs: how will the virus be delivered (intratumoral, perioperative, catheter), and what are the monitoring and biosafety steps?

- Which response criteria will we use (e.g., immune‑adapted criteria that account for pseudoprogression)?

- What practical supports (rehab, infection prevention, seizure care) will be in place during treatment?

Key takeaways

- CAR‑T is established for several blood cancers; solid‑tumor CAR‑T remains investigational.

- Oncolytic viruses are approved for melanoma (and conditionally for glioma in Japan) and are advancing in trials for difficult solid tumors, often in combination with checkpoint inhibitors.

- The best outcomes come from experienced centers with robust monitoring and access to clinical studies aligned with your tumor biology and personal goals.

References (no links)

- U.S. FDA and EMA summaries on approved CAR‑T products (CD19, BCMA) and talimogene laherparepvec (T‑VEC)

- Japanese regulatory communications on conditional approval of G47Δ/teserpaturev for malignant glioma

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) and European guidelines on cellular therapy and immune‑response assessment

- Society for Neuro‑Oncology (SNO) and Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer (SITC) – overviews of OVs and CAR‑T trials

- Peer‑reviewed reviews in major oncology journals (e.g., Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology, The Lancet Oncology, Neuro‑Oncology)

Disclaimer: This guide provides general information and is not a substitute for professional medical advice. Treatment decisions should be made with your care team.